One issue I have been finding in some analyses posted online is that they lack a bit of depth. Some of these projects use existing techniques to showcase a simple task, which is fine for a demonstration of technical knowledge. However, this nature also unfortunately simplifies the picture of data science to just using predictive techniques and machine learning when there is a much larger spectrum to explore such as how you frame a business question to a data problem, or when it is appropriate to apply predictive learning or use another method. On the other hand, I’m also seeing an issue where in practice, a lot of data analysis is still done by hand crawling through lots of SQL queries. There should be a better way we can do analytics with a more data science centric approach in our region. Consider this problem:

When you first approach a business and offer data analytics service, and you’re asked to advise on what to do for a data science strategy, how do you even begin to approach this? What do you even predict?

To give an example of a different approach, let’s try to solve this with an example dataset taken from Kaggle assuming the business wants us to use this. I would like to extend the usual approach of illustrating techniques to something more detailed that allows us to look end to end on how data science could work from a problem based approach on analytics and how we apply our tools. Now, we know from this dataset that

- This data is from an E-Commerce platform, specializing in electronic consumer goods as there is shipping and a large catalog of items.

- Located in India. Their data from 2015-2016 consists of mostly sales, and some high level marketing spend on a monthly basis.

Let’s focus on what questions the business needs to answer first. This is the first step of solving any problem, which is figuring out what is there to solve first. It’s not very productive to build a solution first if you don’t have any idea what you’re trying to solve. Let’s hold our horses and not jump to AI first.

I see many data analysts wanting to get deep into machine learning, and they try to fit a use case to their model before clarifying a good problem statement, when that’s not a very efficient way to tackle the problem. Sometimes machine learning is applicable, and even then, one of the most important questions to ask is what kind of model you want to build, which circles back to the use case question again. Oftentimes, if we don’t ask the right questions, we get a mismatch to the company with the methodology because the company is interested in another problem and the model does not end up delivering large value to either party, so you have to either re-formulate the model or scrap it.

Returning to the problem, the company will have some guidance in terms of what they would want to optimize, or metrics that they want to look at. In the absence of that guidance, first look at the primary metrics of the business first, as this is what drives the primary health of the business. For us, these would be spending, (volume and amount) and customer satisfaction. From these, we can then try to figure out the business questions and find solutions to those problems. The question then drills down to, do we have the data to even conduct such an analysis?

| Metric | Problem | Solution | Issues |

|---|---|---|---|

| Revenue / Spending | How do we increase spending? | Pricing engine that adjust promos and prices based on customer attributes. | No customer level data. |

| Revenue / Spending | How do we increase spending? / Increase customer satisfaction | Recommendation engine to match products to customer. | No customer level data. Product level data is minimal. Unable to see dropoffs from purchases as we only have purchase data. |

| Revenue / Spending | Understanding what causes spending to increase? | Causal inference - analysis on features via A/B testing and experiments | We only have purchases data, Not feasible to do A/B testing |

| $ Marketing spend | How do we get more efficient use of marketing? | Customer segmentation clustering for better campaign targeting. | No customer level data |

| Customer LTV | How do we increase customer satisfaction? | Predict whether a delivery will be late given attributes of the delivery and try to contact customer based on that, or offer follow up care. | No delivery vendor level data. No customer complaints data or NPS score per customer that indicates which delivery had issues. |

The above seems to indicate that we can’t build many predictive models and that experimentations would also be limited if there is no data. While we could use external data to try to create a solution that we could adapt here, the amount of missing data here would suggest that the delivery time of the project would be quite long. However, we can still help our client by understanding their purchases data better via causal inference and understand the trends, and main reasons of customer purchases. From this, they could focus and experiment on these findings in the future. This would be something they can do immediately.

A causal inference based approach

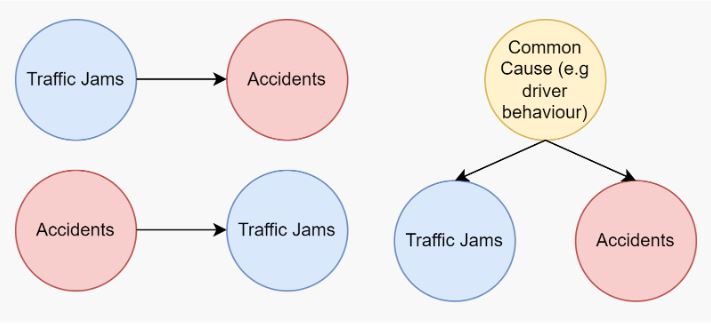

Usually, when we try to make statements about causation, we want to use an A/B test where we have a treatment and control group to design experiments. The reason being that when we observe that C correlates with D, we can’t definitively say C causes D. It could be C causes D, D and C have a common cause as well. Take as illustration, traffic jams and accidents:

Whereas with an A/B test, we can actually control the effect and understand this for different subgroups. In our case, all our data is historical data, and we can’t perform A/B tests on data that has already occurred (say changing discounts to see their impact on revenue). We can, though, perform observational studies and attempt to estimate some of these effects.

If we have a good idea based on domain knowledge on how the causation works and we have a rich enough sample space to simulate what differences in treatment could look like assuming other fields stay constant , we can use models to learn from our existing data what the ‘supposed’ behavior could look like, and make conclusions based on that. This is the whole idea of specifying a structural causal model.

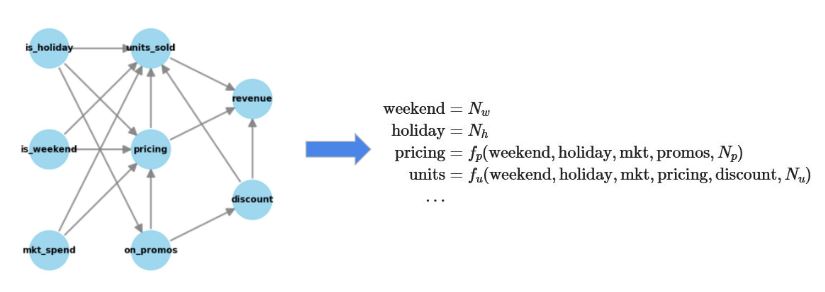

A structural causal model attempts to simulate causal relations by specifying probabilistic models for each feature. We can also input our assumptions on how the causal structure works by incorporating it into a DAG. For example, recall the question that we are trying to answer here: What causes customer spending to increase? We want this model to be designed in such a way we understand from our set of data points what influences revenue. The diagram below outlines our suspected relationship between features and their influence on revenue as a DAG (left) and we will use this to model how business has been operating with our data points with our SCM (right)

In here, \(N_x\) represents noise that we see in our features that causes some of the randomness and cannot be attributed to other features and the functions \(f_x\), represent how the individual terms may interact together. We interpret the model as follows: we can think of pricing as caused by weekend, holidays, marketing terms and some additional other small factors which we denote as noise, and the causal interaction is modeled with a certain function \(f_p\). The model specified, we can perform a regression using our available data to estimate the noise and build some of the \(f_x\), possibly via machine learning algorithms. This model then allows us to explore the data and draw inferences for the business. I will only give an outline here. For more details, you can refer to the notebooks here.

1. Estimate feature contribution

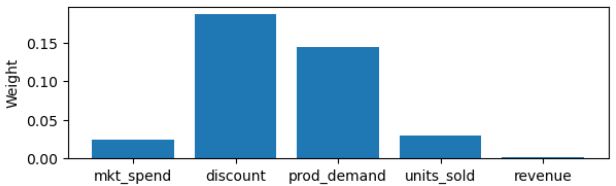

If we observe in the above diagram, revenue has many causal components influencing it, such as the total pricing, marketing spend, or discounts or the units sold. How do we attribute fairly the weight of each independent factor here (e.g is the weight of discounts higher or the base price of the item higher)? With our model, we can estimate the attribution of variance of certain features on the final outcome via Shapley value analysis based on varying different features within our model.

The above chart indicates that for the product in question, a change in revenue is mostly attributed to discounts and product demand. After that, the units sold and marketing spend have roughly equal weight (Shapley values). Using this, we identify that discounting is the key area of interest that we want the business to focus on for the future and we can quantify how much trust we should put into this decision.

2. Advanced simulations

Let’s say we wanted to see what happens if we increase discounts for a specific product. While we can’t conduct an experiment, could we still predict what would happen to total spending in the population on average if we were to say give an 0.3% additional discount on average? The SCM allows us to feed such interventions into the model and then simulate what could theoretically happen and provides us with some estimates of confidence intervals as well. In this case, if we perform the pseudo-experiment, we may see:

% increase GMV median ~ 3.30

95% CI ~ [-24.07, 32.41]

So there is more than likely going to be a positive effect of additional discounts on our product, although the confidence intervals can range quite widely as well, which tells us that it might be worth as a next step to conduct an experiment to confirm the positive effect that we see in the simulation to try to control the risk here.

3. Anomaly attribution

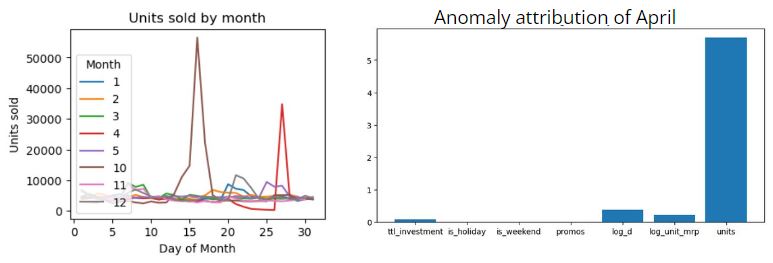

SHAP analysis on the model also allows us to compare what was the cause of differences between a normal day and an anomaly by specifying the feature in question that pulled up the value. For example, notice in our use case, we had a spike in units sold by month for the month of April (red).

By running SHAP on the model with the April data point, we can see that our current existing features do not explain the anomaly in April, which means there is something else going on here. One could imagine that if we ran this in production as an automated system for the company in the future, it could help to reduce the search space to look for anomalies or not.

Question of model fit

Given that we’re starting to draw conclusions from our model, we should probably ask how valid our model is. After all, a model needs to have a good fit in order to be meaningful. I approached this by specifying a more traditional linear mixed model that attempts to model change in units sold and try to draw inferences on that and compare them to the ones that we’ve obtained from the SCM model.

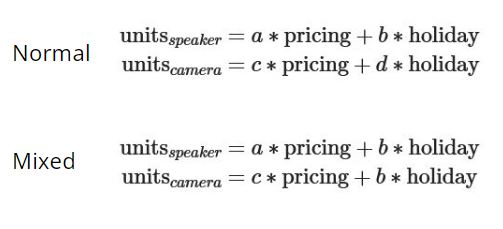

The idea of a linear mixed model is that it’s a generalization of linear regression, but allows us to specify the effects at different levels of interaction between the weights/coefficients of the models. For example, we may not want to model one average effect for discount on the whole, and instead split it by each product market because customers have different habits per product (since we may run into issues with Simpson’s paradox).

One model specification might be that we split our data by product and we produce 10-20 linear regression models, 1 for each product, that models every feature and its effect on how much it increases the unit purchased on a product level. However, the effect from holiday may not be dependent on the different types of products, and instead of one effect per product, I can just summarize them with one general effect on all 20 models and incorporate that into the model. We are in this sense, “mixing” the levels of aggregation here on product and overall level, The model can then be ‘trained’ together and share this information throughout.

Observe with a mixed model, we have one less coefficient d, that models the second holiday effect because it is shared throughout all models.

By having this linear mixed model, it allows us to verify our estimates in our SCM (they should share similar estimate ranges if we’ve specified models correctly). In terms of interpreting the weights/coefficients, they allow us to compare the relative importance of terms on our variables of interest, assuming that they are scaled correctly, and we do find that they match our findings that discount is the most important thing that the business should look at the current moment. A more detailed exploration of this can be found in this example by PyMC.

Conclusions

I’ve written up the results of the analysis in the slides here for more reference and the code details here. In short, using the two models above, we’ve concluded that they should focus on the following.

- Given discounts have the most weight, they should start conducting experiments here with products that have the highest revenue (DSLR Cameras and Speakers)

- Given marketing has not hit saturation point yet, we recommend them to increase their marketing budget.

I made the point in here some time ago that, we in data analytics, should aim to broaden our field and this case study hopefully will give some insight and new avenues for existing product analytics to explore if they haven’t already, and shed some light on causal inference which may be a way to elevate A/B testing and experimentation to the next level. Most importantly, it has to be tied back to the business problem and we can be creative and clever in devising solutions to solve business problems besides resorting to standard data segmentation and checks. In the future, I’d also like to discuss more techniques in this area such as propensity scores (PSM) and specifying correct models as well. With a lot of focus on AI today, it’s easy to forget that there are other ways a data scientist can still achieve value by exploring tools that they have.

Post Script

I’d like to share a few thoughts after using the pyWhy/Bayesian model libraries for this case study in terms of my experience of using these.

SCM modeling via PyWhy

- Most of the causal model understanding came from domain knowledge. In the case where this is not available, it may be more difficult to use this to learn the structure of the model.

- The most useful features were feature attribution and the simulations. This allows us to not look at just one final outcome, but even the features themselves in terms of their causes and explore other dimensions that may not be possible using a traditional algorithm.

- The anomaly attribution is more useful when there are small things to check. I think this provides a way to possibly automate attribution, but is more useful if we have a pre-existing understanding of the system.

- Ultimately, the whole process is still constrained by data availability. The library allowed us to work with more limited sets of data where full prediction is not possible and pinpoint some of the limitations. For instance, there was still a large amount of unexplained data from unit purchases, and this suggests that we need more dimensions of data to look at the problem.

Bayesian via PyMC

- This offers quite a huge range of flexibility in terms of specifying models and then proceeding to test their validity.

- In terms of understanding the library and ease of use, this definitely is slightly easier than using the doWhy library to learn, interpret and pick up. The more tricky part comes with mastery and specifying the correct feature relationships and priors to test our beliefs here.

References

- PyWhy

- PyMC

- Causal Reasoning: Fundamentals and Machine Learning Applications. Emre Kiciman, Amit Sharma.

- Notebooks and Code